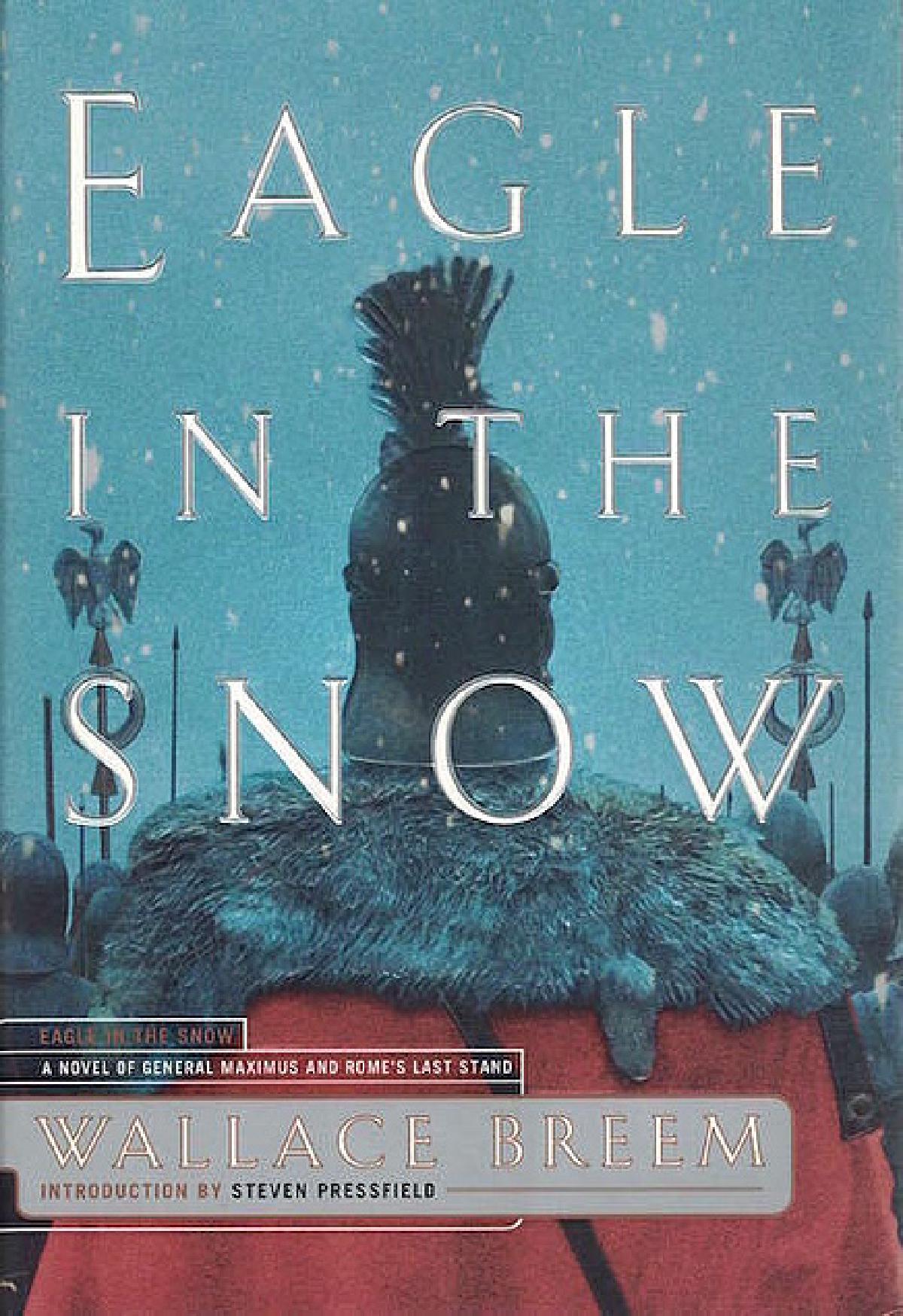

I’m re-reading an old historical fiction classic, Eagle in the Snow by Wallace Breem. Think Bernard Cornwell or Steven Pressfield. Fantastic book, and lovely cover art as well.

Lo and behold, I (re)discover that Steven Pressfield, perhaps my favorite author, wrote an introduction. He deftly captures the essence of great historical fiction. It is short enough I feel ok about posting it in its entirety. Aspirations for historical fiction writers.

Historical fiction has always been a literary stepchild. It’s thought of as a genre, like the Western or the detective story, and not a particularly lofty genre at that. It rarely wins prizes. It takes a Robert Graves or a Mary Renault or a Patrick O’Brian to endow it with stature. It shouldn’t be this way.

Consider the difficulties the writer faces when he ventures into the past. Before he even sits down to think, he has to master the historical material—to learn who’s who, what’s what, where’s where. That’s hard enough. Beyond that, he must reconstitute this world for the reader with such vivid authenticity as to transport him to another time and place and make him believe it. That’s even harder.

Next, he must craft credible, multidimensional characters and bring them to life in a story that’s compelling, involving and true to its era (in other words, to do the same thing a contemporary novelist does, only, like Ginger Rogers dancing with Fred Astaire, in high heels and backwards.) By the time a writer is operating at this level, he’s really cooking.

Beyond that, comes the next plateau: to found the story upon a genuine moral, ethical or spiritual theme, to make it truly “about” something— something that is not only true to the historical epoch in which the work is set, but something relevant and vital to our contemporary era. That’s the Holy Grail of historical fiction.

When a writer pulls off this four-part hat trick, as Wallace Breem does in Eagle in the Snow, I want to say his work transcends the genre, but it’s better than that; it employs the genre in the highest way it was intended. It doesn’t hark back to the past for the fun or color of the trip; it uses the past, a very specific past, to illuminate a very specific present.

Wallace Breem is a master of this, as he shows brilliantly and (seemingly) effortlessly in Eagle in the Snow. Breem’s story feels as if it were written then, not now; the reader experiences it then, not now. Yet when it’s over, the reader knows it is about now, not then, and that it could not have been set in any other place or time. Wallace Breem belongs on that very short list of writers whose work elevates historical fiction beyond the genre and sets it alongside the best writing of any kind, in any period.

–STEVEN PRESSFIELD